|

| The library at Kremsmünster Abbey, from a book plate (ex libris) in the Saint John's Collections. |

The following article is dedicated to the monastic community at Kremsmünster Abbey in gratitude for their enthusiastic support in 1965 that started HMML's whole process of manuscript preservation through photography.

The Work (Finally) Begins: Getting Started in Kremsmünster (April 1965)

On this date, April 16, 1965, the first actual photography took place in all of HMML's preservation work. The very first manuscript filmed was a collection of sermons, which happens to share the primary position in the Kremsmünster collection, where it is listed as "Codex Cremifanensis 1." Unfortunately, we have no photographs of Father Oliver working in Kremsmuenster, except one possibly of him with his colleague for technical support, Eugene Power.Father Oliver describes Kremsmünster in his second Progress Report (June 1965):

“The Abbey of Kremsmünster was founded in 777 by Herzog Tassilo III of Bavaria, as a religious shrine to commemorate the sad event of the death of his son, who was killed in the area by a wild boar during a hunting expedition. Except for the tragic years of 1939-45, when the entire monastic community was ejected by the German warlords from the north from what had been its home for over a thousand years, the Abbey has enjoyed an unbroken and flourishing existence. During the Nazi occupation the entire manuscript collection of the Abbey was transferred elsewhere. Thanks to the generous cooperation from American military forces, the collection was recovered shortly after the war, with the loss of only a few codices. It goes without saying that their precious manuscript collection is now dearer to the Benedictine monks than ever before.”

|

| The Mirror of Human Salvation from the Kremsmünster Monastery Library. From color microfilm photographed by Father Oliver Kapsner and his team in 1965. |

Father Oliver Kapsner’s brief synopsis of Kremsmünster Abbey’s history does little justice to the work that he and his colleagues accomplished in getting this first microfilming site set up and running smoothly. After his brief respite at the Benedictine house of Einsiedeln (Switzerland) during the Christmas season, Father Oliver returned to the logistical planning for the microfilming. Already in January he met with the director of University Microfilms, Mr. Eugene Power:

“Mr. Power telephoned again a few days ago, now wants me to meet him in Vienna next week, to inspect the electric power situation in a few abbeys before moving in with equipment. He almost upset the applecart by suggesting using women employees. I has specifically mentioned in my letter to him “Women excluded.” Yet he dares to come back with the idea, as if I have not had enough trouble as it is to get entrée. Is there a shortage of the male species in America? To get at the manuscripts we must enter intimate parts of the monastery in most instances.” (Father Oliver to Father Colman, January 18, 1965; from Einsiedeln)

|

| Biblia pauperum from the Kremsmuenster Monastery Library. From color microfilm photographed by Father Oliver Kapsner and his team in 1965. |

Fortunately, today women are no longer “excluded” from HMML’s work—quite the contrary. Many of our overseas photographers (from the 1980’s to the present) have been women. However, the world was still quite different in 1960’s Austria, and such access into libraries within all-male monasteries was too difficult for Father Oliver to manage. Indeed, finding appropriate personnel was just one of the problems he faced in these early days:

“Mr. Power came to meet me in Vienna last week. Together we visited four of the abbeys on our schedule. While some of my problems have been solved, his are now beginning, namely: variety of manuscripts and bindings, variety of electricity (three of the four abbeys do not have sufficient amperes on their regular circuit), right manpower, patience. He thinks we may be able to start in about five or six weeks, at Kremsmünster.” (Father Oliver to Father Colman, February 5, 1965; Schottenstift, Vienna)

Many other aspects of the work were ironed out during the months of February and March 1965, such as the annual renewal of the contract with University Microfilms for the technical aspects of the project, and the storage of negative copies of the films at the company’s Ann Arbor offices. The films would be developed in Austria, and then shipped to Michigan, where two positive copies would be made—one for Saint John’s and one for the owning library. Father Oliver also discussed the difficulties of hiring camera operators from the United States, since they would likely feel isolated in a German-speaking world. In light of the difficulties related to unusual work spaces, varying electrical supply, and the materials themselves, Mr. Eugene Power also suggested to Father Oliver that he should expect an operator to produce an average of about 1000 exposures per day, not the 1500 that was a common output at locations in the United States.

|

| The prophet Joel from a Latin Bible in the Kremsmünster Monastery Library. From color microfilm photographed by Father Oliver Kapsner and his team in 1965. |

In a letter to Father Oliver, dated February 9, 1965, Father Colman informs him that the Knights of Columbus have decided to donate $10,000 to help start the project. Along with this gift came a request that Father Oliver provide photos of the work being done. This is likely the ultimate impulse for the documentary photographs taken at Seitenstetten Monastery later in 1965 (See: They Shoot Manuscripts, Don’t They?). Father Colman’s secretary (Elaine Vogel) appended her own note to the letter that the Knights of Columbus had requested a thousand copies of Father Oliver’s first Progress Report to distribute to its members.

Finally, in the second week of April 1965, Father Oliver was able to report to Father Colman directly from Kremsmünster:

“At long last Mr. Power of University Microfilms arrived in Austria in order to start the microfilm project. The last time he was here (Feb. 1) the flu bug hit him. It apparently took a long time to recover from it back in the States, but fortunately he did recover. The Austrian President Schärf was also hit by the flu (Grippe) a week after Mr. Power, and another week later he was buried. …”

|

| Codex Cremifanensis (Schatzkasten) 6. Vaticinia et imagines Ioachimi abbatis Florensis Calabriae ... From color microfilm photographed by Father Oliver Kapsner and his team in 1965. |

“Anyhow he is here now. But what a headache to get this project off the ground in a foreign country. We have spent three days now in the offices of lawyers, customs, insurance agency, bank, Kodak Co., Volkswagen Co. Yesterday I sat three hours in a lawyer’s office (we are a foreign corporation, with foreign equipment and foreign employee in this highly socialized state). Yesterday we also spent three hours in the customs office, and still did not get the equipment (12 pieces) cleared. We have to return to customs today, and if we get the equipment we can finally proceed tomorrow to Kremsmünster, to wrestle with the local problems there. Holy Week is obviously not the best time to proceed there, but we must go when the going is possible. Yesterday we also received our Volkswagen Kombi (small truck with removable seats). And I will be responsible for the whole work and works. Brother, if my next letter to you comes from jail, I hope you are disposed to send me some food parcels. Anyhow, keep your fingers crossed. The people at the Nationalbibliothek admire the scope of our project and our courage, which may be a polite Austrian way of saying we may be presumptuous. They know that we will not be doing this work in a convenient laboratory, but under a variety of local conditions. However, they would very much like to have a positive microfilm copy of all the manuscripts in Austrian monasteries. That could be settled when the Austrian project is done.” (Father Oliver to Father Colman, April 13, 1965; from Kremsmünster)

.jpg) |

| Father Oliver Kapsner, OSB, and Eugene Power from University Microfilms, in front of the van used to transport the microfilming equipment and team. Photo taken in Austria. |

He also reports in this note the appreciation at Kremsmünster for the gift copy of Father Colman’s history of Saint John’s, Worship and work. He also notes with pride that he has added four more monasteries to his list of microfilming partners! In the midst of the busy-ness of getting the equipment and team in place, Father Oliver did not write for almost two weeks, at which point he could finally report the start of the actual microfilming:

“Here is a continuation of my last epistle, and of our work and problems. It will still take all of a month till we really know how we are doing, not till after University Microfilms has received our products and approves our work.

Probably the very first photograph taken for all of HMML's preservation

work--the identification plate on the first reel of film shot.

We arrived here with staff and equipment on Wednesday of Holy Week [April 14, 1965]. It took two days to get set up. Electricity will be quite a problem wherever we go. We really needed Mr. Power on the spot to put all the parts together and pull this through; he really knows his stuff. By Good Friday afternoon, of all days, the first photographs could be taken, and work continued till Saturday noon. Easter Sunday Mr. Power left, feeling certain that we could manage, and obviously fed up with this weather. The two camera operators, one from abroad, the other an Austrian, are trying their best, but need experience to handle these tricky medieval manuscripts. The films are developed in Vienna, 120 miles away, and one shipment has now been returned. We ship every day. It would be a catastroph[e] to really lose any films in the mail. We need twice as much work space as I had thought, and it may not be so simple to get that much in all the monasteries. Besides being responsible for the work, workers and equipment, I prepare the materials, and my typed bibliographical entry has to be filmed first. In addition, in my eagerness to get the project on the way, I volunteered to Mr. Power to inspect the films, but I must leave off on that, as my eyes just can’t stand all day work with old manuscripts and the microfilm reader. Incidentally, have you somebody ready to take over in case I should falter, for as you know, I am no longer a spring chicken, and neither this life nor this work is a picnic. Like anybody else, I can just try my best and leave the rest in the hands of the Lord.” …

Codex Cremifanensis 1 (HMML Project no. 1) - a collection of sermons.

The manuscript is about 400 leaves long!

“The first week of April looked like spring, then Austrian winter returned and hasn’t let up since. The big hills outside my window are covered with white snow, the real stuff. The newspaper headlines for April 22 read: König Winter kehrt wieder zurück [King Winter comes back]. And on April 24 the newspaper headlines announced: Regen, Regen, Regen—und dauernde Kälte [Rain, Rain, Rain--and lasting cold]. There are floods in eastern Austria and in Burgenland (Abbot Alcuin’s homeland). Imaging all this in Austria at this time of year. I still wear my overcoat in choir (their own monks do the same) and in the library workroom, as neither place is heated. The natives are hardened to all this, though they do not like this return of winter a bit. Brother, if I ever live through all this and survive, I may become so tough that you may have to use an axe to dismiss me from this vale of tears. The friendly Austrian attitude continues through all this, which is indeed a blessing and a help.” (Father Oliver to Father Colman, April 26, 1965; from Kremsmünster)

|

| The Ascension from a Latin Bible in the Kremsmünster Monastery Library. From color microfilm photographed by Father Oliver Kapsner and his team in 1965. |

Father Colman did his part by supporting the work from afar—he sent a copy of his history of Saint John’s (Worship and Work) to the abbot and community at Kremsmünster. They responded enthusiastically and noted that they are trying to help Father Oliver in any way they can:

“Es freut uns alle, dass P. Oliver bei uns ist und er mit dem Fortgang der Arbeiten zufrieden sein kann. Soweit wir können, unterstützen wir die Arbeiten.” [We are all glad that Father Oliver is staying with us and that he is satisfied with the progress of the work. We try to help with his tasks in any way we can.] (Albert Bruckmayr, OSB, to Father Colman Barry, OSB; May 8, 1965; from Kremsmünster)

Finally, on June 8, 1965, Father Oliver reported to Father Colman from Kremsmünster:

“Today we finish the photographing of manuscripts at Kremsmünster. Enclosed is my second Progress Report, which embodies a job actually completed, and for which St. John’s should be having the films, all of them, before too long, probably another month before the last ones will arrive from University Microfilms. We shipped the last ones there today.”

|

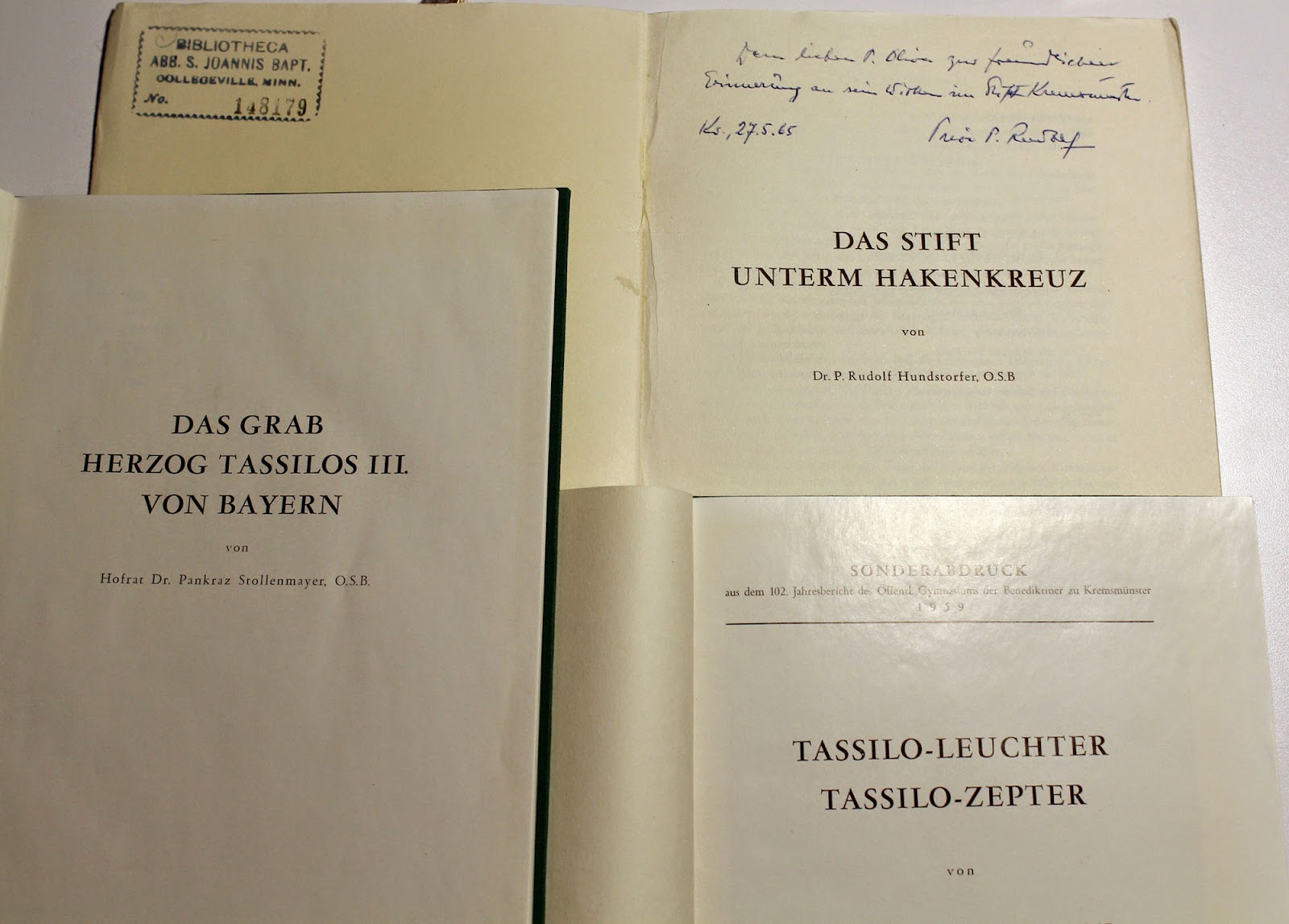

| Books given to Father Oliver during his stay at Kremsmünster . |

He noted as well the irony that the Abbey’s most famous manuscript—the Codex Millenarius—was away on exhibit. He was able to microfilm this landmark manuscript later during the Austrian project. From Kremsmünster, Father Oliver and his team continued on to Lambach Abbey and shortly thereafter to Seitenstetten. After several months of delays, the photographic preservation of manuscripts was now (finally) in full swing!

|

| The Codex Millenarius (the evangelist Matthew) from the Kremsmünster Monastery Library. From color microfilm photographed by Father Oliver Kapsner and his team in 1965. |

Thanks to the community at Kremsmünster Abbey and their then abbot, Albert Bruckmayr, HMML had a successful start to its now fifty-year-old mission of preserving manuscripts through photography. With the help of partners like those at Kremsmünster , HMML has been able to pursue an international undertaking unimaginable to Father Oliver when the first pages were microfilmed!